Kliph Nesteroff: September 1968 - you started writing for the Kraft Music Hall specials. The first one starred Alan King with guests Don Rickles and Sugar Ray Robinson.

Sam Bobrick: They hired us for the summertime and they liked us so much that they kept us. We took over the winter show for a year. They wanted to come back but the show was in New York and we were living in California, so it was too hard. Dwight Hemion and Gary Smith were the producers.

Very, very nice guys. Dwight Hemion was probably one of the best directors I have ever worked with on television. We did a summer show for them too - the Don Ho show. It was a vacation in Hawaii. I spent six weeks in Hawaii.

Kliph Nesteroff: Danny Simon was also on staff...

Sam Bobrick: Danny was the greatest first draft man. He would write a first draft that was great. But he would doubt himself. He would keep rewriting it. He was working on a play. It was called the Shadow Only Knows. It was about two brothers and one lives in the shadow of the other. It was about him and Doc! He rewrote it so much it eventually became The Convertible Girl and it ended up being about a gentile girl who converts to Judaism!

Kliph Nesteroff: (laughs)

Sam Bobrick: How did he get from there to here? Well, he always doubted himself! But he was a wonderful writer. He would work with Marty Ragaway and they were always bickering. But as soon as we heard his typewriter stop we would run in and grab the pages. We knew were going to be great. We were all in New York.

Kliph Nesteroff: One of the guests on one of those Alan King Kraft specials was Buddy Hackett.

Sam Bobrick: He and Alan were friends. You hear terrible stories about him being a very difficult man, but the funniest man. Buddy Hackett was very sensitive. You never knew what he was thinking, but he was always thinking something. We knew he had the temperament and Alan had no temperament at all. Alan King was really a prince to work with. He'd work with the writers, roll up his sleeves and sit there and pound out the show.

We did a show, Ron and I were the producers and writers. We did a sketch where Buddy and Alan, friends in life, how they were when they were children. There was a little kid to play Alan and a really fat kid to play Buddy. That made Buddy mad. He came up to me. He said, "Who's that fat kid!" I knew there was trouble. I said, "What fat kid?" He said, "You don't see a fat kid?" I said, "No." He said, "Oh. Okay." And that was that. He didn't want a fat kid playing him.

Most comics are very, very tortured and they're just a strange group. They are so conflicted and so jealous and so many things, "Why him! Why not me?" I found it very difficult being around comics, especially the ones that didn't make it or couldn't make it or were on the periphery. They were tortured, so tortured. Buddy Hackett was a very tortured man.

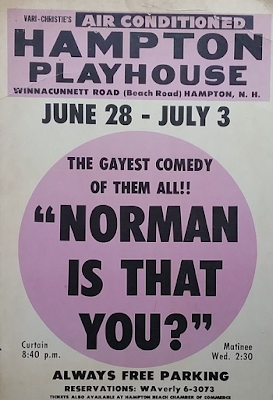

Kliph Nesteroff: You wrote Norman Is That You? It has gone down in history as having the most bizarre second life of any Broadway production...

Sam Bobrick: Broadway hated us because we were television writers. There was a snobbery in New York. It's still very cliquish. They tore us apart. We thought we had the biggest hit going. The audiences were roaring - roaring. And opening night we got killed by everyone. They accused us of writing a television show.

Two things happened. It was the first comedy about homosexuals. The premise is a father from Cleveland comes to New York and discovers his son is gay. The son takes off and the father is stuck with the other gay guy. Today it would be politically incorrect, but at the time it was a funny, funny show. The critics were upset that it was a serious subject and they thought it should be treated seriously. Coming from California, you don't treat it seriously.

It was based on people we knew. The next day the reviews were in the paper and they killed us. There was a story about an axe murderer on the front page. A guy hit a woman in the head with an axe and threw her down a shaft. And then I read our reviews. I thought, "My God, they were nicer to the axe murderer than they were to us." You would have thought we had done the worst thing in the world. You needed the papers in order for a show to succeed in those days. We had a novice producer and he just left us in the lurch. We ended the show. I think it played a week.

Kliph Nesteroff: Twelve shows.

Sam Bobrick: The rights reverted back to us.

Kliph Nesteroff: Despite it closing after twelve shows, George Schlatter bought the film rights immediately.

Sam Bobrick: Yeah, he read the play on an airplane and he bought the film rights. I think Billy Wilder offered us money and when the reviews came out he withdrew it. George read it and bought it. There was a French producer, Arthur something. His wife was going shopping and he didn't want to go along so he went to our play. We closed on Saturday night and he saw it Saturday afternoon. He saw the show and said, "I want this for a movie." Then he found out the rights were sold, so he said, "Well, then I want it as a play in Paris." He put it on in Paris and it ran five years! Then it played all over Europe and about forty different countries. It became a big, big hit.

Kliph Nesteroff: What did you think of the George Schlatter film?

Sam Bobrick: I hated it. Did you ever see it?

Kliph Nesteroff: I did.

Sam Bobrick: Oh my God. We wrote a script - we wrote one script and I guess they rewrote it. I remember when I went to see it at the MGM. I said, "Where did the puppets come from!?"

Kliph Nesteroff: Wayland Flowers and Madame.

Sam Bobrick: And then at the end... it had an ending where the guy becomes straight! I said, 'Oh, shit.' I never watched it again. That movie came out and then I was involved with another disaster called the Last Remake of Beau Geste. Marty Feldman had trouble trying to work out the story.

He was handled by George Shapiro so I worked with him to work out the story. I didn't do the movie with him. He did it with a friend and he was going to direct it. My mother was in town and I got her tickets for a preview screening. I arranged for my mother to go see the Last Remake of Beau Geste. Now she had already seen the movie of Norman Is That You and never said anything about it. So she came home and I said, "Hi mom, how was it?" She said, "You know, son, maybe movies aren't for you."

I thought that was funny. The movies were rough. I did another one with Gary Coleman and they shot a new ending for it and it looked totally different. People had completely different hairstyles. I was no longer involved with it, but you know, it was just terrible. My movie experiences weren't so terrific, but I liked writing them.

Kliph Nesteroff: Did you work with George Schlatter?

Sam Bobrick: We did, but then the project laid around for seven years. We were hoping it would revert back to us. He did it on videotape or something - they didn't use film. It was a cheap kind of thing. I was working on another show at the time, so I couldn't get involved with it. It was just a disaster, I thought. I hated it.

Kliph Nesteroff: You worked on the Tim Conway Comedy Hour with Ron Clark, Rudy DeLuca....

Sam Bobrick: Rudy Deluca, Barry Levinson and Craig Nelson. They were writers. They were working on a local station. We read some of their material and it was wonderful. We gave them a name. We called them the Third Bananas. They were wonderful. Barry became a famous director and Craig became a famous actor.

There were only thirteen episodes, but we really had fun doing it. We were doing outrageous sketches. We were doing the kind of sketches on that show that they eventually did on Saturday Night Live. Crazy sketches. Tim played Hitler as a football coach and the costume he wore was Charlie Chaplin's from the Great Dictator. He was the exact size as Charlie Chaplin. We did a sketch with mountain climbers trying to climb a floor. Just outrageous things. CBS wasn't prepared for it and we followed another variety show starring Jim Nabors. We didn't have much of an audience. I know we had a lot of young kids watching it and Tim was wonderful to work with. DeLuca and Levinson would write sketches and were brilliant, brilliant guys.

Kliph Nesteroff: Every show Conway had got canceled quickly and eventually he had vanity license plates that said Thirteen Weeks.

Sam Bobrick: Thirteen Weeks, yeah. Then he did another one about a detective. Ron produced that one. I was in New York rewriting the musical The Wiz, so I didn't do that one. Tim was so talented. He could fall up a flight of stairs.

Kliph Nesteroff: April 1970 you wrote The Bob Goulet Show starring Robert Goulet. Bob Hope was a guest.

Sam Bobrick: Yes, he was. I forgot I even wrote that show. Bob Hope only sang a song. The deal was he didn't want money, but he would do it if Goulet did three appearances on his show. Three for one. The sad thing was Hope was on our show and he was wonderful, but he never ended up hiring Goulet.

We went to Goulet's house and he was so nice. I think Hope sang a song from Camelot and he was really terrific and he wouldn't go home. After the show he just wanted to hang around. Norman Rosemont was the producer. He was Bob Goulet's manager. Marty Passetta directed. He was from the Smothers Brothers show.

Kliph Nesteroff: You created a sitcom called Love and Cement.

Sam Bobrick: Oh gosh, we never sold it. It was a tenement situation comedy. A guy living in Brooklyn or something. We did a pilot for Paul Lynde. We had to spend some time with him. People loved him from Hollywood Squares. We would go to lunch and people would follow us out like the Pied Piper. They just loved him, but we didn't want to stay with the show. We just did the pilot and left.

Kliph Nesteroff: Paul Lynde played gay without being out - and the premise was that he was the head of a family with wife and kids.

Sam Bobrick: Yeah, well, those days you couldn't do anything. We tried to sell a pilot about a divorced couple and they said no. You had a lot of restrictions whereas now there are none. It's easier to write now because you can say and do anything, but we couldn't do this, couldn't do that. You couldn't show bellybuttons. On the show I Dream of Jeannie they had to cover up her bellybutton.

Kliph Nesteroff: How about Pat Paulsen...

Sam Bobrick: He was a very unassuming and very grateful guy. I knew him and his wife. Pat didn't know how funny he was. He was doing a play of mine once and called me up. It was opening the next night. He said, "Is it funny, Sam? Is it funny?" I said, "No, Pat, it's a drama." He believed me. But when he went on the laughs were tremendous and he called me back and he was mad with me (laughs).

But he was a good friend. Toward the end it was difficult for him and I would write things for him to help. His manager was one of my best friends - Neil Rosen. He was a writer as well. He had a summer theater and Neil had me direct some plays featuring Paulsen up there. We got to know each other even more so than when we were on the Smothers Brothers.

He thought funny. Sometimes you're amazed by who is funny and who is not funny. Pat was just funny without knowing he was funny. He did the Ice House and I would go to see him. He was good, he was always good. I think the Smothers met him at the Ice House. Tommy and Dickie - I remember seeing them at the Hollywood Bowl and they were so funny. They were so talented.

Tommy was kind of in charge of the team. Dickie just enjoyed his life with his race cars. Tommy was the older one, I guess. He took care of it. They were just a great, great team when they were young. I didn't keep up with them when they were older. God, this is fun, Kliph. I'm amazed with what is coming back to me.

Go Back to Part One with Sam Bobrick

No comments:

Post a Comment